If you made it here, many congratulations! You may have only one or two topic-related courses left before the dissertation journey begins. Take a little breather, if possible, as the last few steps you must traverse are work-intensive and require several iterations before you reach the final defense.

As a reminder, here is the curriculum layout for year three of the program:

Year 3/4 Classes:

Consulting Learning Practicum

Dissertation Seminar (We are here)

Doctoral Written Comprehensive Exam

Directed Research (This repeats for up to 3 more terms, carrying into a 4th year if needed)

Dissertation Oral Defense (Non-credit)

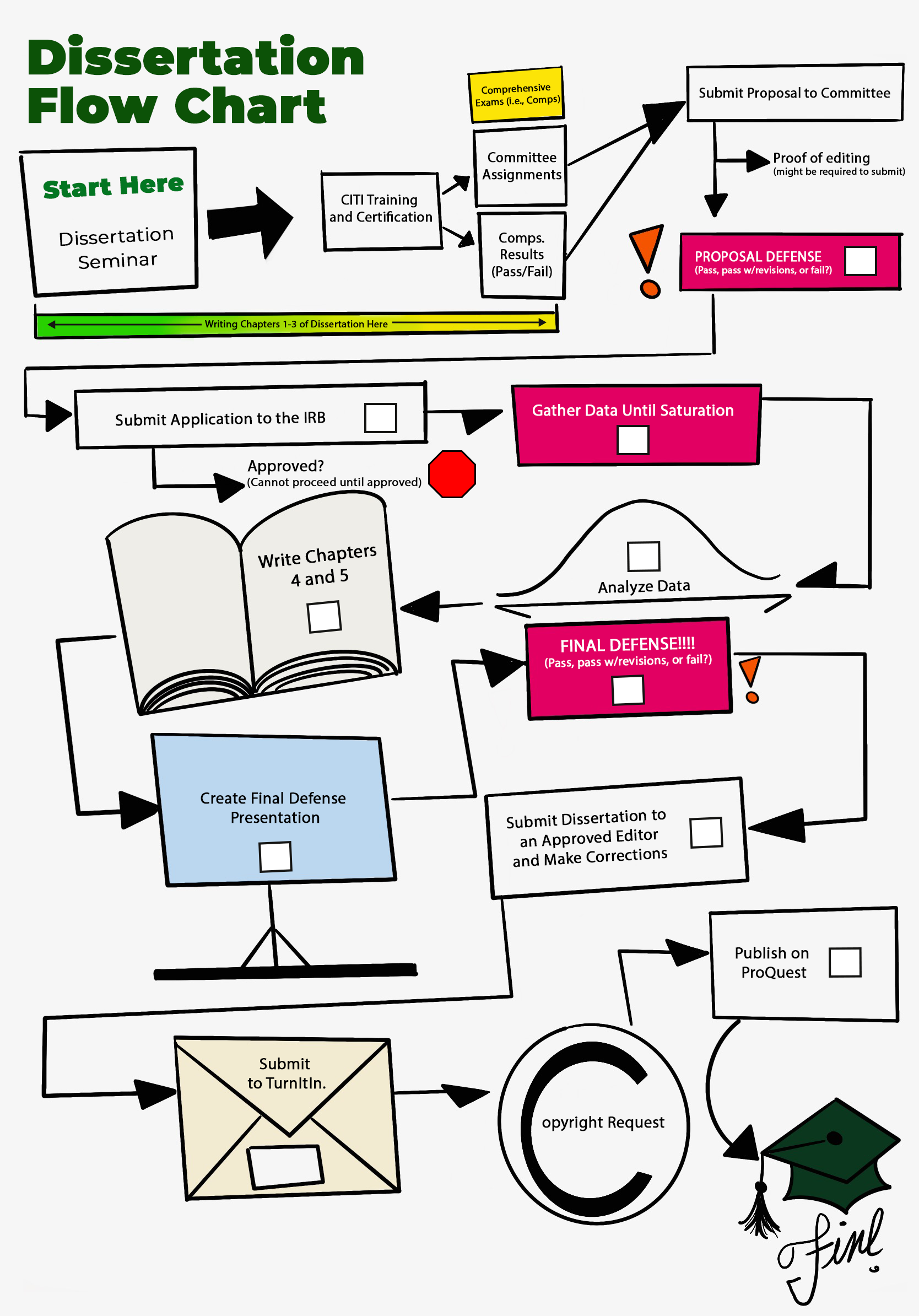

Since I'm a visual person, at the beginning of my dissertation adventure, I drew a flow chart that I could refer to as I took each step, I share this with you in hopes that it will aid your journey, but likely your process will deviate slightly dependent on the design of the curriculum you have chosen. Since the dissertation is the main event within this series, the adventure will be broken into a post for each course and the tasking contained within them.

For the grand overview, here is the flow chart:

The adventure began in the first course focused on the dissertation, the Dissertation Seminar class. This class had two assignment categories and a training certification program to be completed to satisfy the course requirements. Weekly module writings prompted discussion regarding our progress and drafting the first three chapters of the dissertation for the Comprehensive Exams (AKA Comps.; more on Comps. in the next post).

Writing three chapters felt like a challenge to me at this juncture, but I was reminded that it is an iterative process (Agile mindsets are helpful here). What I produced would not be perfect. In instances like these, I am reminded of a simple truth from Nadya Ichinomiya in an online training session arranged for my students (but I get as much out of these sessions as they do):

Perfection is an illusion. There will always be mistakes, and you'll catch them over time and revisions, but your dissertation will still need improvement at the end of the day. Further, differences in interpretation will create discord among the experts in your respective field, thereby throwing your work under scrutiny. (Thus is the nature of academia.) Because of this underlying nature, attempting to write something that will be universally accepted and praised is a fruitless endeavor.

Strive for objectivity here, and remember to keep your personal opinions elsewhere. Theories are welcome, but only after you have done the legwork by researching what is out there first. The important thing is to start researching and writing. Then, keep going. Writing a dissertation is a marathon, not a sprint. That said, it might now be helpful to overview what Chapters 1-3 are all about. With no further ado:

Chapter 1: Introduction

You'll know what this chapter is about if you have read anything. The Introduction section (along with most of the writing in a dissertation) is formulaic. Specific areas are expected to be included and vary slightly by your chosen research methodology. In this chapter, you will likely be asked to include the following sections:

Problem Background

Statement of the Problem

Purpose of the Study

Theoretical Framework

Research and Interview Questions (If using a qualitative or mixed methods approach)

Brief Literature Review

Definitions

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

Importance of the Study

Summary

There's an approach that will serve you well here:

First, tell your readers what you're going to tell them

Second, tell them

Finally, tell them what you told them

They may not get it or remember in step one or two, but your odds improve with each reiteration. It's true when people say there is a lot of redundancy in dissertation writing, but it's not without purpose. By the end of writing Chapter 2, you will have stacks (literally) of research supporting an existing theory that you seek to either test or further explore to formulate a new testable hypothesis. Chapter 1 lays the groundwork for the following chapters, provides a contextual overview for the deep dive that lies ahead, and serves as the first step to the method listed above.

Chapter 2: The Literature Review (the DEEP dive)

Did you bring your swimming goggles and snorkel? How about a full diver's tank? This chapter is where you take a plunge and dive deep into the prior studies and research done by those that have gone before you. I hope you bring a snack because you'll need it.

Chapter 2 is often the most extensive and densest in the dissertation. You are looking for the giants whose shoulders you'll eventually stand on. The sectioning and organization will vary widely and is dependent on the following:

The area you have chosen to research

The associated variables or phenomena of your study

The context surrounding the subjects of your study

The stacking design of the research to build up to the gap in the research you seek to fill (i.e., your contribution to the universal body of knowledge or the pimple you are creating, as noted in a prior post)

For example, my chapter 2 was about 70 pages, which can be considered light compared to other dissertations you'd find as you conduct your research. I recommend looking at other dissertations (as was recommended to me by my chair) to see how the authors organized the timelines and structures of their research so that you can build a relevant and practical skeleton for your own Chapter 2.

Pro-tip: Build an outline (framework) of your Chapter 2 and run it by your professor in the introductory course to determine if any key areas are missing BEFORE jumping into the writing. Additionally, ensure your framework is supported by past research from experts in the same field.

This chapter (along with chapters 3 and 4) tells the reader (step two from the above approach) what research and theories are out there, what areas of consensus and discord there are among scholars, and after examining the body of research, what gaps exist that can be furthered.

Three areas will likely need to be covered for each variable, amongst others that come from your committee or advisors:

The historical perspective includes:

Evolution of the variables or phenomena

Past work by seminal scholars, leading experts, and thought leaders.

Past theoretical frameworks concerning your topic

Current studies (for my program, this was defined as within the past five years)

The current state of the variables or phenomena

Recent studies across all methodologies (Quantitative, Qualitative, or Mixed-Methods)

Background on the subjects (participants) of your study

Industry (if work-related)

Variables concerning your theory or hypothesis

Population information

Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, or Environmental (i.e., PESTLE) factors affecting your selected population

Summary

Chapter 3: Methodology (your "Research Cake" Recipe)

This chapter informs the reader about your research approach and design from the perspective that you are employing and the underlying theory(ies) to the mitigation methods used to reduce the impact of biases infiltrating the study. Think of this section like a giant research recipe, where you're outlining the ingredients and cooking techniques employed to bake this "research cake" (Yum!). Sections of this chapter may include:

Study Theory and Worldview

Purpose of the Study (reiterated from Chapter 1)

Research Design

Population Information

Respective Sample Information (including sample size determinants)

Data Collection Methods

Data Analysis Methods

Validity, Reliability, and Measurement Issues

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

Summary

Expect your institution's review board (IRB) to scrutinize this section when submitting your application. These folks seek to ensure that prospective participants are protected from adverse impact and safeguarded by anonymity or identification obfuscation methods. (We'll talk about this in another post.)

Back to the Class

Now that we've briefly covered the chapters, let's talk about the experience of this class and what to do to be successful. The dissertation seminar class again was about getting the rough draft "out" to be refined and resubmitted in Comps. Comps are a make-or-break class with no feedback; it's just you doing the work on a tight deadline. Accordingly, doing as much prep work and soliciting feedback here before Comps is recommended.

Here is where you write the first iteration (if you've not been doing it already, as advised by Dr. Dool in a prior post) of the chapters that will be submitted for your proposal defense in a later course, assuming you've passed Comps. The course also required completing research training and certification from the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI).

Hitting the Books (i.e., the internet, university library, and actual books)

Do you recall when I said the reference list is like a shopping list? This technique can help start you along your journey. Another approach is to create a question framework about your variables so that you begin to search for publications that can answer your questions. My strategy was to start with the questions and then use the reference sections to guide my journey, going deeper and deeper with each iteration. I also looked in the references for commonly sourced articles or scholars. The more these people or writings popped up, the more I considered them foundational or seminal research.

Note: Google Scholar is great for this but use a critical lens when including articles.

Each article lists a source count so you can more clearly see how significant the author or article is in the scope of the larger conversation.

You will likely hit articles that are locked behind a paywall. Fun fact: Authors may have to pay for their work to be freely accessible to the public; I didn't discover this until after I submitted my work to ProQuest, which may explain why you are hitting a paywall. This point is where searching across multiple databases may yield what you're looking for without paying. I recommend a one-two-punch method:

Search across multiple databases.

If unsuccessful, then reach out to your institution's librarians (again, these folks wield research magic and are excited to help you)

If still unsuccessful, then reach out to the author directly.

Writing, writing, and more writing…

At some point, you will have read so much about your topic that information may start to blend; this is where being organized becomes critical. My safeguard was the cover sheet and file organization methods I mentioned earlier. I read an article once, reread it, and filled out the summary sheet. Then I would write a paragraph or two using the sheet and package it up under a folder for the corresponding variable and the methodology used in the study. Does this process seem like a little much? It could be, but it worked for my thought process and helped me write quicker and more fluidly. To each their own.

Another note about writing concerns paraphrasing another scholar's work. You should not leave room for accidentally plagiarizing (I assume no one that has made it to this point intentionally plagiarizes.) Please remember that even when paraphrasing, YOU STILL NEED TO SOURCE AND CITE the work, which leads me to a personal motto:

One Personal Motto

If there was ever any room for something to be interpreted as "I said that" when discussing another's research, I cited it (probably more than needed, but better to be cautious in these situations). I also ran my work through Grammarly's plagiarism checker to be sure. It saved me a lot of headaches, and I hope it helps you.

I can't think of any more to add!

If you run out of things to write, this is likely an indicator you need to read more but check with your professor to see what areas need to be further built upon. Questions to ask yourself:

Did I cover the history and evolution of the variables from their genesis to their current states?

Did I include the seminal authors and leading experts in the field?

Did I discuss areas on consensus?

Did I highlight and contrast differing views on the variables' nature, interaction, or sequence of events?

Is there a clear gap that creates an opportunity for my study?

What areas could be more straightforward?

What areas need further research to demonstrate due diligence?

Did my professor note areas I need to revise?

The goal of this process is to be as prepared for Comps as possible. Will you be 100% ready? No, likely not. But even 70-80% ready increases your potential for success when it rolls around.

We'll talk about comps and dissertation committee selection in the next leg of this adventure. Til' next time!